Meet Me in St. Louis (1944) is uncompromising in its colors, treating skintones with the reddish blush of a Norman Rockwell, with cutting yellows and clear blues.

What Is The Look?

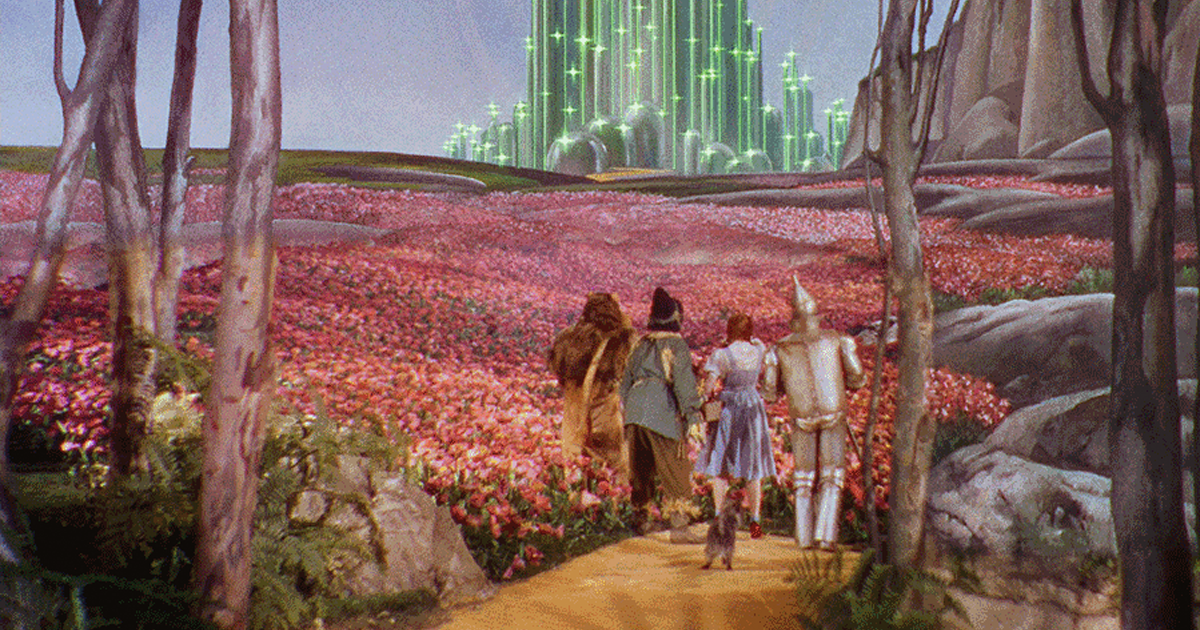

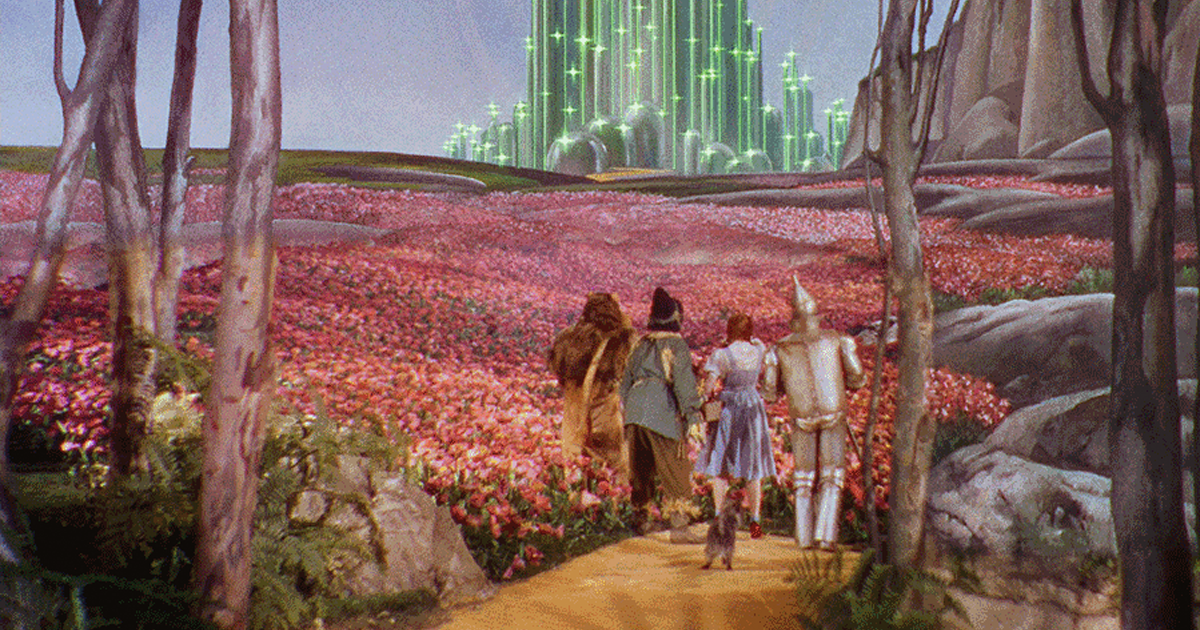

Wizard of Oz (1939)

and

Meet Me In St. Louis (1944)

, and later films like

Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964)

and

Suspiria (1977)

. Its saturation looks candy-like but not garish (the sort of painful deep-fried look from cranking up an image's saturation), creating an image on screen that feels somehow larger, more vibrant, than life. Like so many iconic treatments of art, this brilliant artifice is a look shaped by negotiations with its technology, in this case, a color film process called 3-strip Technicolor. I'll attempt to break down the components of this look without diving into the technicalities.

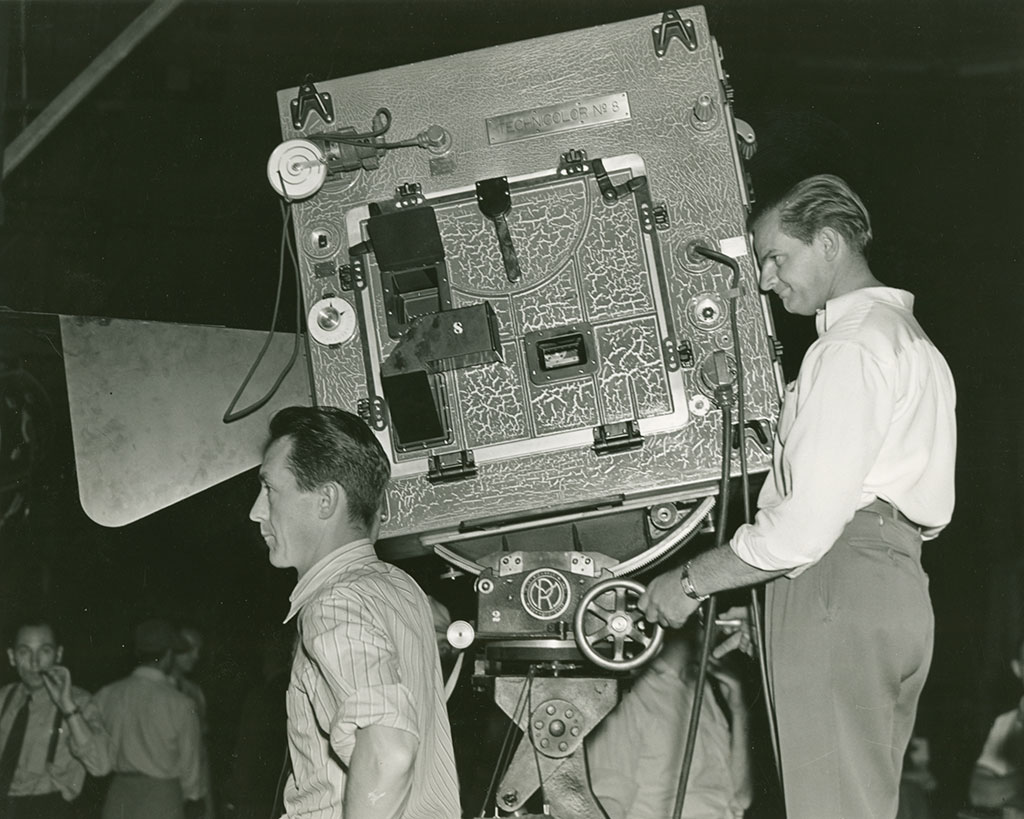

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ec/75/ec758fc5-e571-42e3-ae4a-525f4e2968dc/nmah-jn2014-3761.jpg)

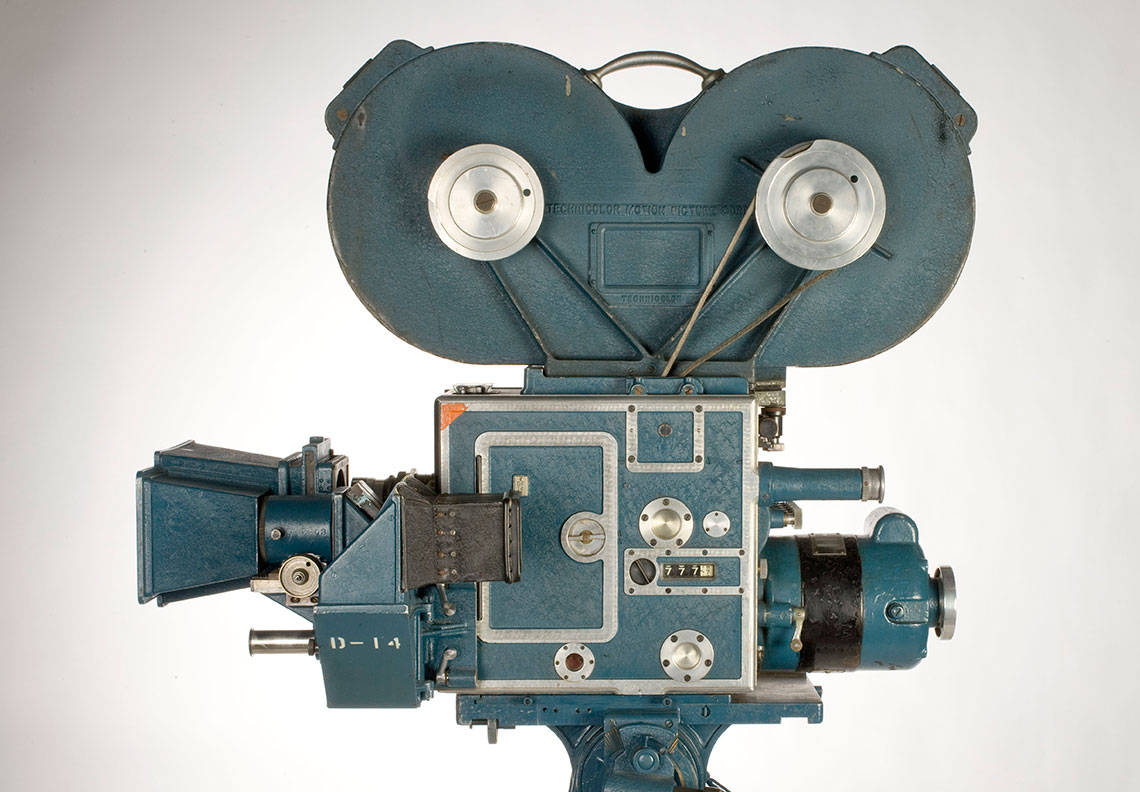

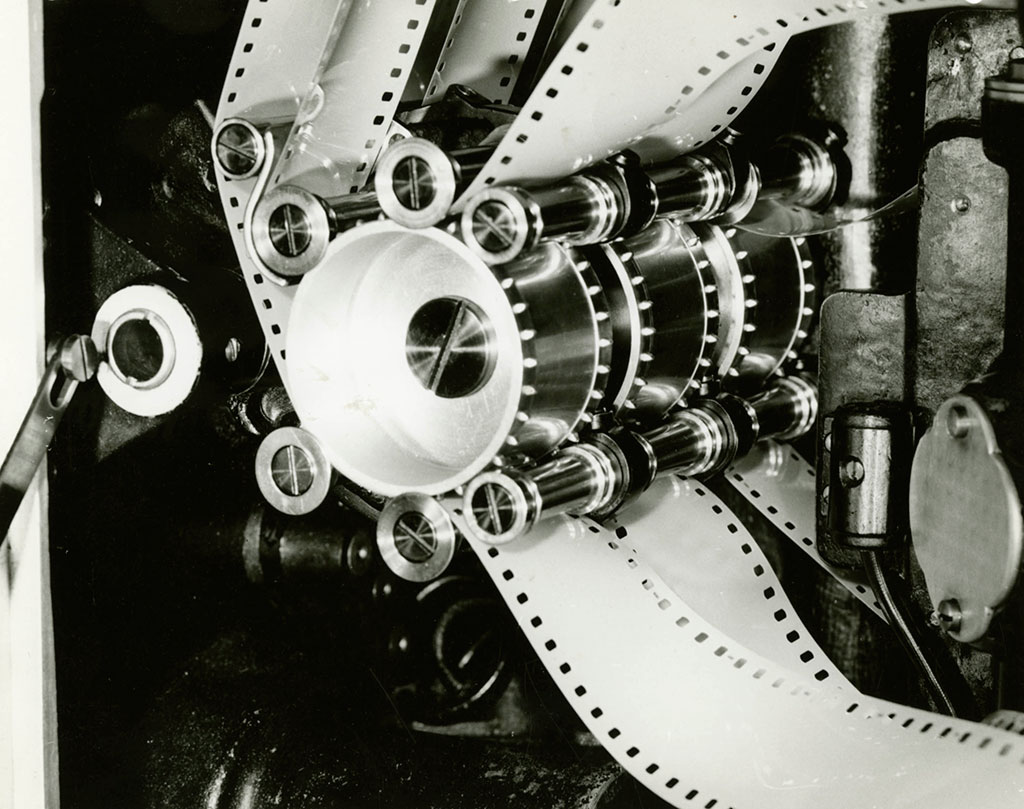

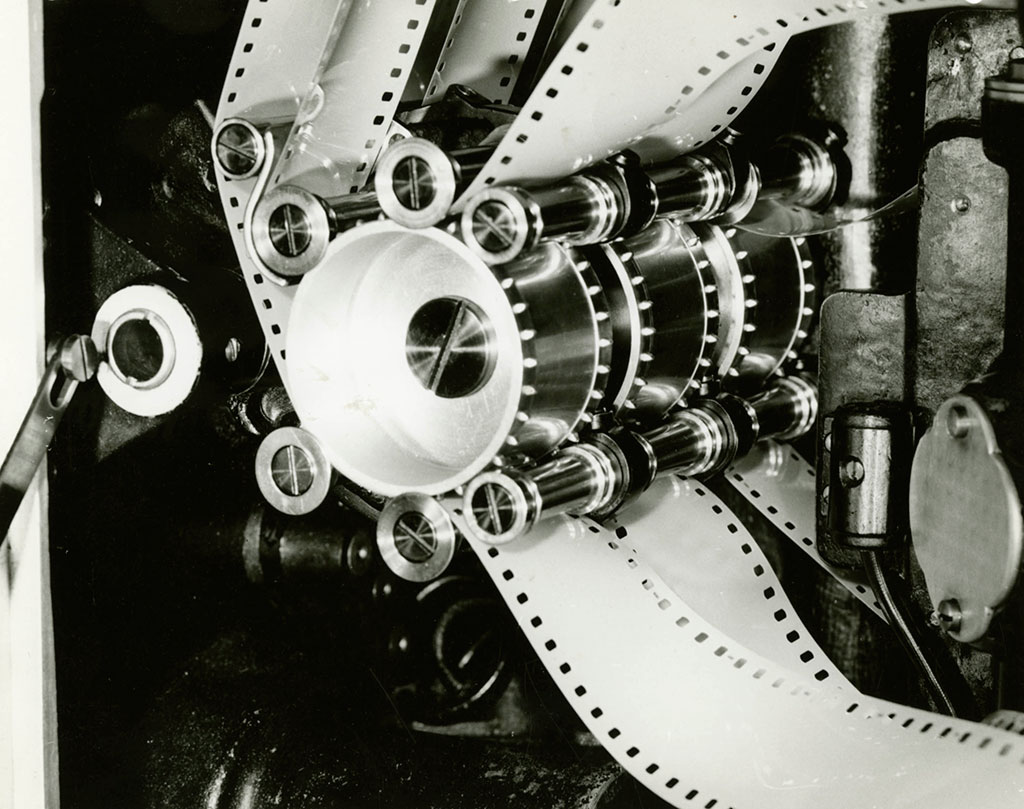

The Technicolor camera mounted on a crane. The camera itself is incased in a much larger soundproof box, as the camera was so loud from its many moving parts.

3-Strip Technicolor

leap of color fidelity The dulled colours of the previous 2-strip technique

The dulled colours of the previous 2-strip technique

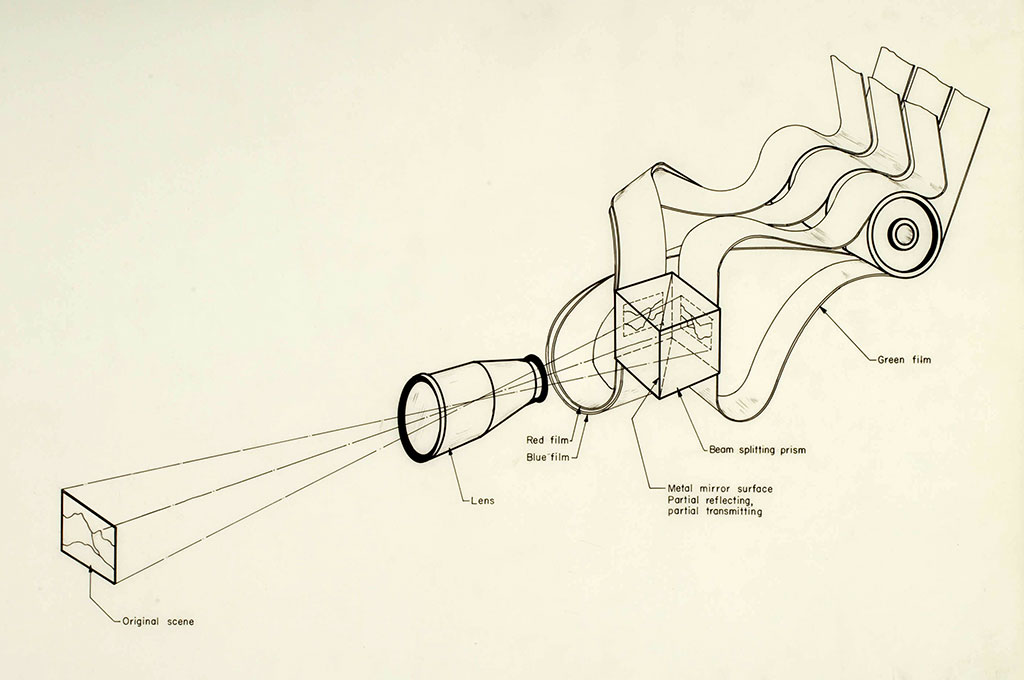

. This technique is named 3-Strip from its core feature of filming on three strips of film at once. When the specialized  The dulled colours of the previous 2-strip technique

The dulled colours of the previous 2-strip techniqueTechnicolor camera George Eastman Museum

George Eastman Museum

films a shot, it  George Eastman Museum

George Eastman Museumsplits the incoming image George Eastman Museum

George Eastman Museum

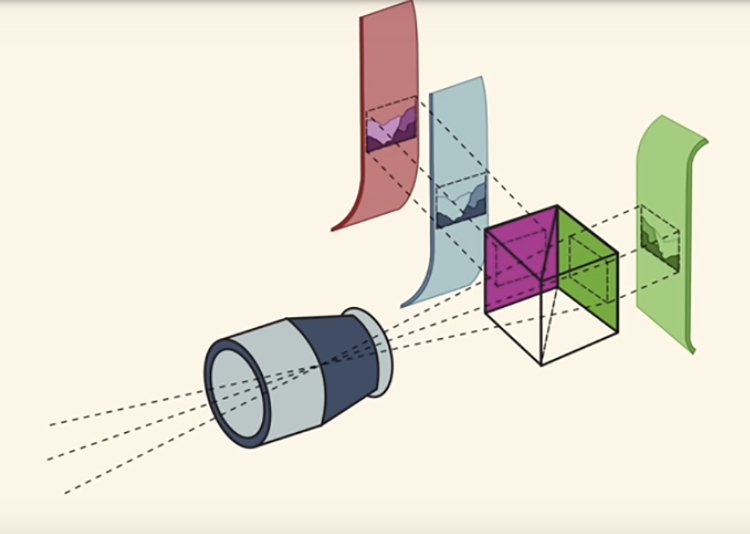

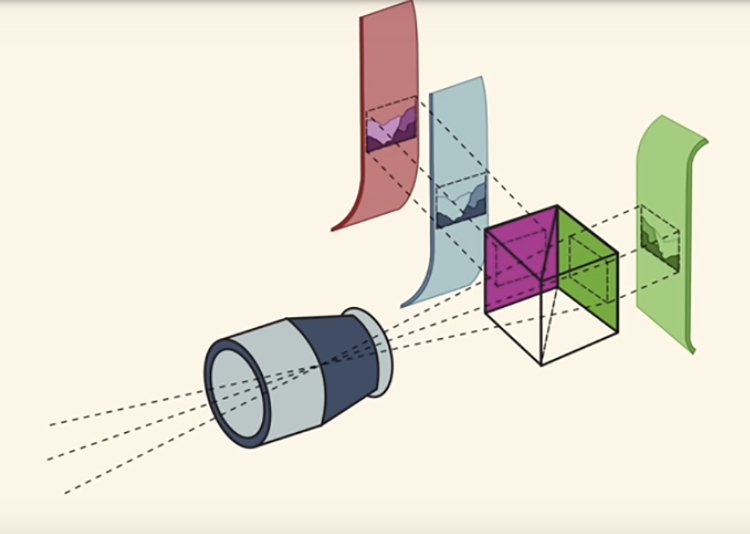

into separate paths, through three different colored lens (red, green, and blue), onto three strips of film, to create  George Eastman Museum

George Eastman Museumthree black-and-white reels George Eastman Museum

George Eastman Museum

of the same footage, but  George Eastman Museum

George Eastman Museumonly capturing its specified colour George Eastman Museum

George Eastman Museum

. These three reels are developed in a Technicolor lab and undergo a dyeing process to invert their colours (from Red/Blue/Yellow into Cyan/Magenta/Yellow), and glued overtop one another, creating a final coloured film strip. There is an excellent video by The 8-Bit Guy who approximates this process digitally. George Eastman Museum

George Eastman Museumthis lecture elaborates on additive (RGB) vs subtractive (CMY) color theory

), but the key is in the downstream effects to this lengthy and specific process.Link to Youtuve Video on Additive Vs Subtractive Colour Theory by Greg Danbrooke

From the George Eastman Museum, a diagram demonstrating the image (as dotted lines) passing through the lens and split onto three reels of black and white film that capture only the Red, Green, and Blue rays of the image.

Lights, Lights, Lights, Camera, Action!

basic

, this is controlled by how long the film is exposed to the light, or how bright a scene is to begin with, so you don't have to look at it for long. This is the concept of exposure. Because the Technicolor camera splits the incoming light into three, to reach three separate reels of film, each reel is exposed to a third of what one would expect from a typical one-strip process.Ignoring the concept of aperture

$225,000

in electricity bills and required an everpresent fire inspector. Luckily, the cast only came close to a heatstroke, although others were Apparently $5.7 Million in 2024

hospitalized from burns for unrelated yet typically insane 1939-filmmaking reasons.

A rushed explosion stunt had left the Wicked Witch of the West (and her stunt double) with severe burns to which the actress Margaret Hamilton describes "as though someone had taken off the top of her hand and peeled it back like an orange."

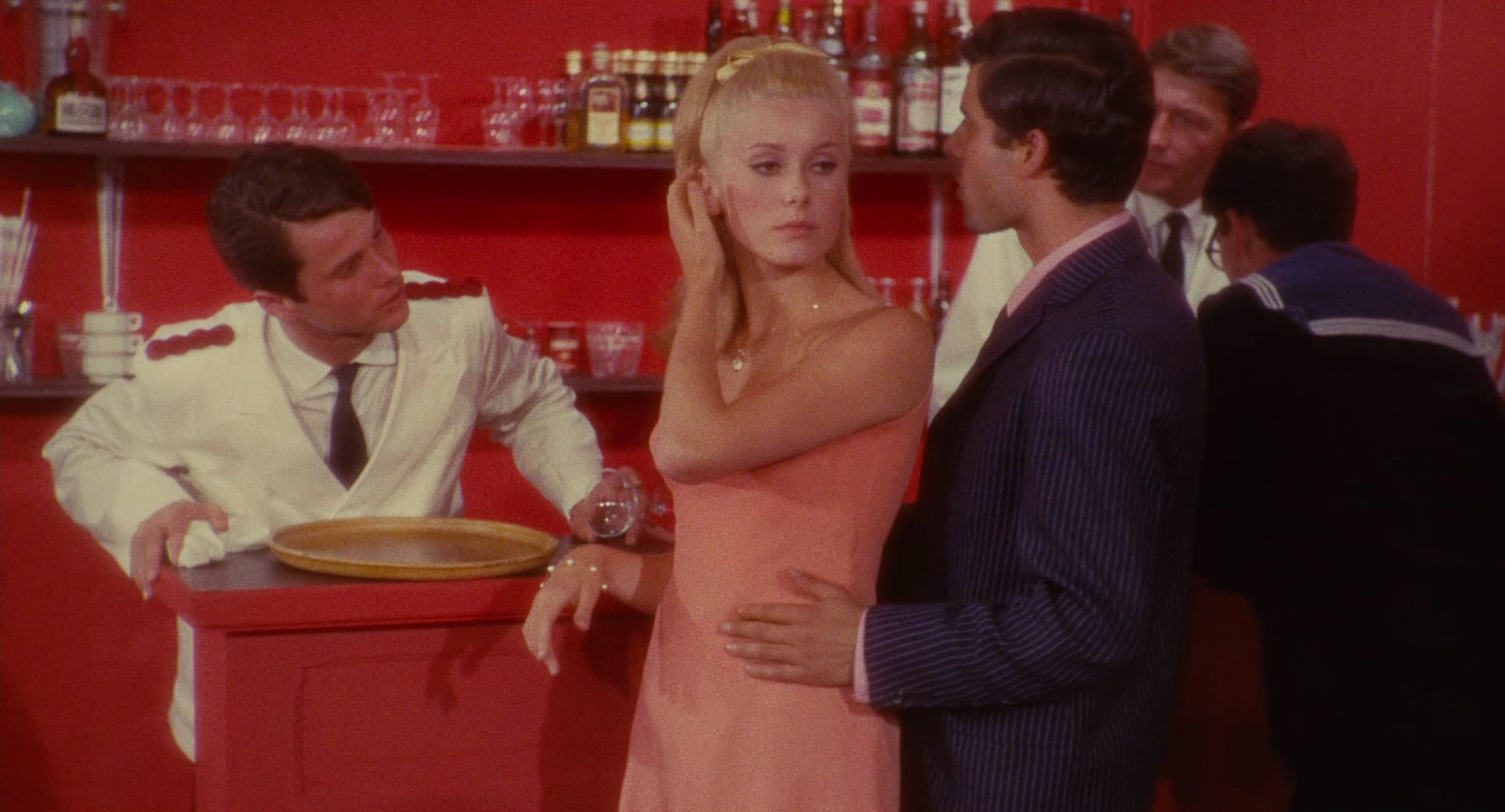

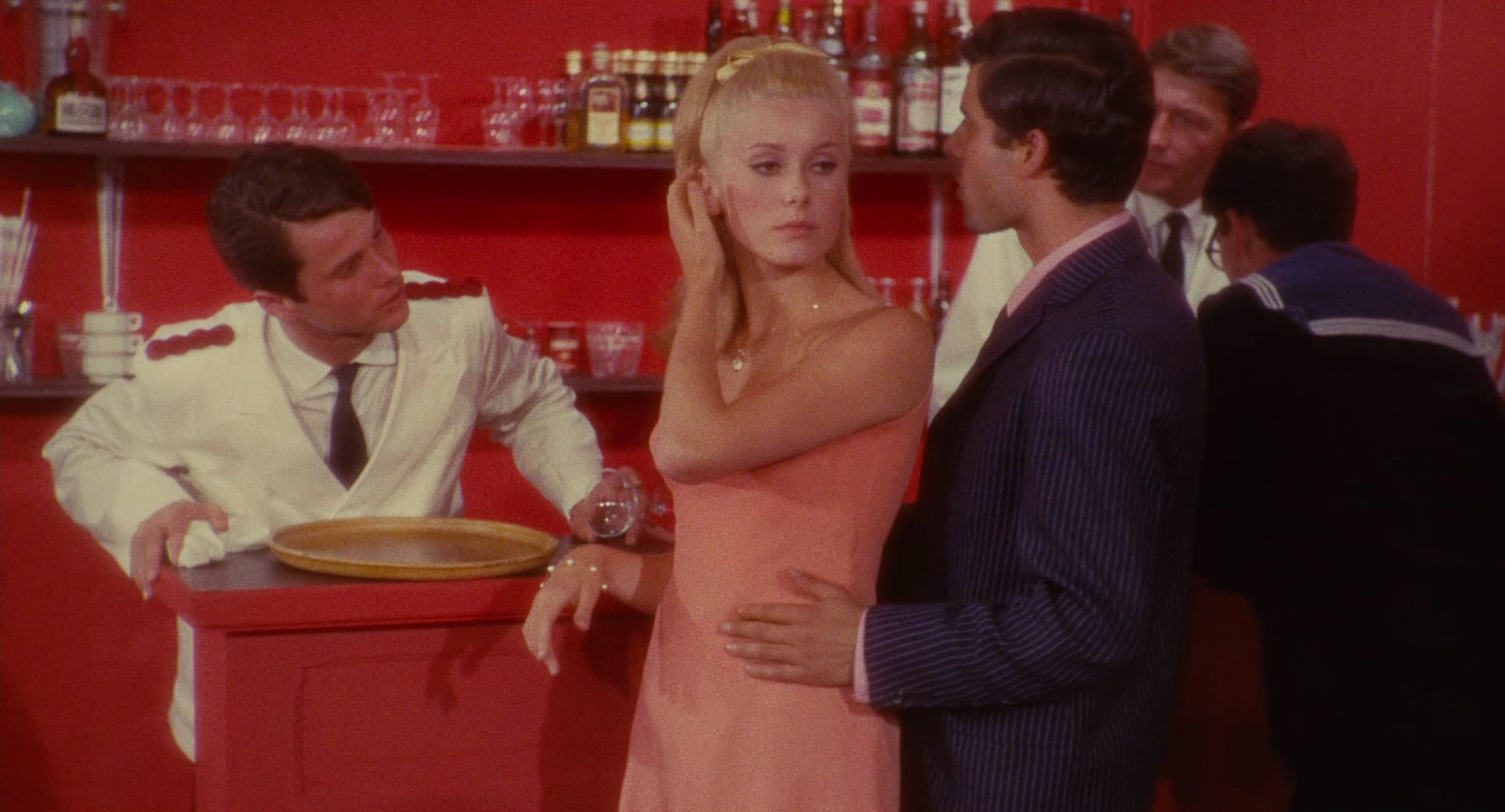

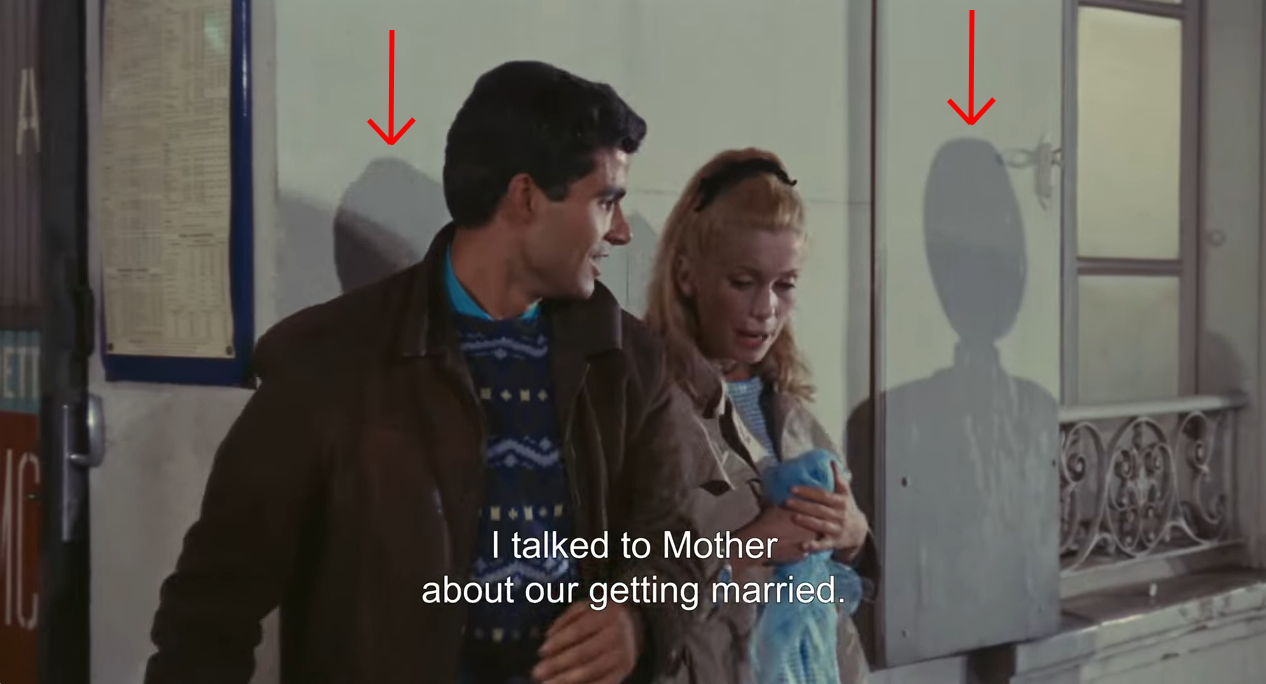

In this scene from Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964), notice how sharp the casted shadows on the walls are. Shadows this clear requires strong direct light, akin to a spotlight, which is still dim enough on-camera to create a night scene, although there are many ways to make a scene bright but still feel like a night shot

We Need To See The Money

unweildy 25 specialty cameras

. The knowledge was so guarded, even Technicolor technicians were prevented from learning the entire process. This trades knowledge lent Technicolor aggressive control over its pricing (The cost of Technicolor for

Goldwyn Follies (1938)

was an estimated $600,000,

Higgins, Scott. “Technology and Aesthetics: Technicolor Cinematography and Design in the Late 1930s.” Film History 11, no. 1 (1999): 55–76

$2 million budget

). With costs that high, production needs to make every penny spent on colour could be seen as justification.Converted for inflation for 2024, that is $13.5 million out of a $45 million budget

matte painted backgrounds Emerald City in The Wizard of Oz (1939)

Emerald City in The Wizard of Oz (1939)

, or vibrant (and sometimes sparkling) costume designs that bordered on cartoonish. Even in Dorothy's Slippers, which were  Emerald City in The Wizard of Oz (1939)

Emerald City in The Wizard of Oz (1939)silver in the source material

, were swapped last minute for sparkling Ruby sequins that flexed its reds against the Yellow Brick Road (although in real life, the slippers are a "Dorothy looked, and gave a little cry of fright. There, indeed, just under the corner of the great beam the house rested on, two feet were sticking out, shod in silver shoes with pointed toes." - The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900)

deeper maroon The Smithsonian, where the shoes are displayed

The Smithsonian, where the shoes are displayed

since they were to be blasted with aformentioned powerful set lights). The Smithsonian, where the shoes are displayed

The Smithsonian, where the shoes are displayed

The iconic red slippers in The Wizard of Oz (1939) really were just to make the most of this highly commercial film.

Technicolor Color Doesn't Fade

Suspiria (1977) has gone through multiple remasters over time, getting crisper with each remaster.

Bonus Material: The Glamour Shot

Meet Me in St. Louis (1944) is interjected with these glamorous portrait shots of Judy Garland, exhibiting all the techniques mentioned. This shot has a strong key-light from the left which is picked up by her eyes and casts a strong shadow on her neck.

shallow depth-of-field

. The subject is lit with a standard three-point-light composed of a 'fill' light that brightens the entire scene (more on this fill later), a 'key' light to show where the main light is coming from (often catching the glint of the eyes and creating the only harsh shadow on the head), and a 'rim' light shone above and behind the subject, carving a white perimeter of the silhouette. The rim light serves the purpose of isolation when, combined with the shallow depth of field, separates the subject from its background in an almost pasted green screen-like manner. This rim creates a halo-like glow (especially against fluffier hair) that is excentuated by techniques of diffusion.A "shallow DoF" creates a blurry background. Think of this as allowing a small or "shallow" degree of what's on screen to be in focus, versus a "deep DoF" which allows for a larger amount to be in focus.

Further Learning & Sources

- The Judy Room: The Wizard of Oz

Production photos of the Wizard of Oz - Smithsonian Magazine - Without This Camera, the Emerald City Would Have Been the Color of Mud

- Vox Video - How Technicolor changed movies (Youtube)

Excellent overview on Technicolor - Greg Danbrooke - Additive Vs Subtractive Colour Theory

Overview of how RGB combines into a full image compared to CMYK - DIT Spot (Archive.org) - 3 Strip Technicolor Look in DaVinci Resolve

- The 8-Bit Guy - Color Photos from a Black and White Camera

Applying the 3-strip process philosophy with a modern black and white camera - In70mm.com - A History of Low Fade Color Print Stocks

History/Explanation of Technicolor's non-fading properties